The Crown Section of the Willamette Meteorite The rarest of collecting opportunities: the ability to acquire |

|||||

|

|||||

The Willamette meteorite is the largest meteorite found in North America. As it was discovered on the surface of Oregon woods, it is believed the meteorite fell in Canada and was deposited in Oregon during the last Ice Age. According to Clackamas Indian tradition, however, the meteorite called “Tomanowos,” or “Heavenly Visitor,” was delivered from the Moon to the Clackamas, and healed and empowered the Native American community in the Willamette Valley since the beginning of time. The Willamette meteorite was “discovered” in 1902 when a miner named Ellis Hughes noticed the meteorite on property adjacent to his own, which belonged to Oregon Iron & Steel. Hughes ingeniously moved the meteorite onto a wagon, and using a horse, cables and capstan, Hughes moved the 15.5 ton mass of nickel-iron over a period of months onto his land and charged the curious a fee to see it. On October 24, 1903 the Portland Oregonian reported Hughes' discovery and the crowds on his front yard swelled.

The Willamette meteorite has been on display at the museum for 102 years—and its tenure has not been a quiet one. It has been a centerpiece in two major exhibit halls and has been touched by an estimated 50 million people—and there have been two additional custody disputes. In 1990, tens of thousands of schoolchildren signed petitions to have the meteorite returned to Oregon. A bill was proposed in support of the schoolchildren’s ambitions in the U.S. Senate and an Oregon congressman advanced the notion of withholding federal funding earmarked for the museum until the meteorite was returned. A concerted effort was made to convince the childrens’ mentors to discontinue their effort--and the childrens’ campaign was suddenly dropped. In 1999, a coalition of tribes of Oregonian Native Americans, The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, filed a claim to have the meteorite returned to Oregon by invoking the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)—typically used to retrieve burial remains and crafted artifacts. In response to the Grand Ronde’s invocation of NAGPRA, the museum filed a lawsuit in federal court in which the Grand Ronde’s claims were contested, and the museum requested a declaratory judgment that the meteorite was museum property. The parties eventually settled out-of-court and the meteorite remains the centerpiece of the museum's Rose Center where there is now signage indicating the meteorite’s spiritual connection to the Grand Ronde’s predecessors. There is also an agreement it can never again be cut.

While a media uproar occurred in 2007 regarding the supposed defacing of the meteorite, such claims are unfounded. When a single meteorite is recovered with no additional specimens from the same event, the meteorite necessarily undergoes subdivision by scientists for analysis. If one looks closely at the mass on exhibit today, the viewer will note other specimens have been removed —of which very little is accounted for. Science was again served when this meteorite was cut in 1997. The curator of the Macovich Collection, Darryl Pitt, noticed unusual bubbling at the margin of an inclusion and contacted an expert in iron meteorites, Dr. John Wasson of UCLA, who in 2007 wrote in part, "These bubbles are fascinating. We cannot remember having seen angular FeS fragments entrained into a eutectic melt before." In September 2010, Dr. John Rubin of UCLA sought to acquire a specimen containing the anomaly for further research and further expressed a desire to write a paper on the same. The last time a specimen of Willamette sold, it brought nearly three times its weight in gold (as of 11/3/10 - $1340/oz). An extremely noteworthy offering, this is a singular specimen of a preeminent meteorite. 246 x 279 x 158mm (9.5 x 11 x 6.25 inches) and 13.399 kilos (29.5 pounds).

Contact for further information: museumcenterpiece@gmail.com

|

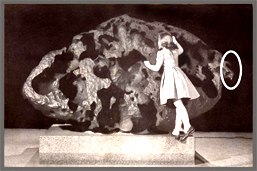

TOP ROW, LEFT

TO RIGHT:

Willamette meteorite shortly after its discovery; Willamette meteorite on

exhibition at 1905 World's Fair.

TOP ROW, LEFT

TO RIGHT:

Willamette meteorite shortly after its discovery; Willamette meteorite on

exhibition at 1905 World's Fair.